Introduction

Almost every C++ programmer knows about opportunity to substitute your own custom allocator for the default of stl containers, but almost no one actually use this opportunity. :)

And I agree, that this feature is become obviously almost unusable when dealing with large enough real projects, especially when a lot of third-party C++ libraries used, and you quickly realize that containers with different allocators are just incompatible with each other.

After all, why custom allocators (for containers) are actually may needed for?

I do not believe that control over memory allocation per container can give at least some benefits. I mean, that control over memory allocation should be done not per container, but per {thread, blocksize} pair. Otherwise, memory obtained from a custom allocator is not shared with other objects of the same size (lead to memory wastage), and there are potential multi-threading issues. So, when you think of usefulness of custom allocators there are more questions than answers.

After all, I thought what if specific pool can be chosen at compile-time when the size of requested memory block is known beforehand. Then, a single application-wide allocator can completely eliminate any need for custom allocators! This idea looks like somewhat unrealistic, but still I decided to try implementing it.

Design Principles

1. Inlining and compile-time size class calculation.

When code of allocation function is small enough, compiler can inline it to eliminate need of call. And also, when size of object is known beforehand, it would be very good if size class (i.e. specific pool to satisfy that allocation request) can be chosen at compile-time. To make this possible, computation of the size class itself should rely only on built-in operators (no asm or external function calls) and must not access any dynamically calculated data. After all, application's source code should be compiled with link-time optimization turned on (/GL for MSVC, -flto for GCC/Clang, and -ipo for ICC) to make possible the inlining of operator new calls. As a sample output, here is a result of compilation of single statement "new std::array<int, 10>":

| Source Code | MSVC 2012 compiler 32-bit asm output | GCC 4.8.1 64-bit asm output |

NOINLINE void *test_function()

{

return new std::array<int, 10>;

}

void *operator new(size_t size) { return ltalloc<true>(size); }

void *operator new(size_t size, const std::nothrow_t&) { return ltalloc<false>(size); }

template <bool throw_> static void *ltalloc(size_t size)

{

unsigned int sizeClass = get_size_class(size); //computed at compile-time

ThreadCache *tc = &threadCache[sizeClass];

FreeBlock *fb = tc->freeList;

if (likely(fb))

{

tc->freeList = fb->next;

tc->counter++;

return fb;

}

else

return fetch_from_central_cache<throw_>(size, tc, sizeClass);

} | mov eax,dword ptr fs:[0000002Ch]

mov edx,dword ptr [eax]

add edx,128h ;296=sizeClass*sizeof(tc[0])

mov eax,dword ptr [edx]

test eax,eax

je L1 ; probability is just about 1%

mov ecx,dword ptr [eax]

inc dword ptr [edx+8]

mov dword ptr [edx],ecx

ret L1:

push 18h ; =24 (size class)

mov ecx,28h ; =40 (bytes size)

call fetch_from_central_cache<1> (0851380h)

add esp,4

ret

| mov rdx,0xffffffffffffe7a0

mov rax,QWORD PTR fs:[rdx+0x240]

test rax,rax

je L1 ; prob 1%

mov rcx,QWORD PTR [rax]

add DWORD PTR fs:[rdx+0x250],0x1

mov QWORD PTR fs:[rdx+0x240],rcx

ret L1:

add rdx,QWORD PTR fs:0x0

mov edi,0x28 ; =40 (bytes size)

lea rsi,[rdx+0x240]

mov edx,0x18 ; =24 (size class)

jmp <_Z24fetch_from_central_cache...>

|

| As you can see, the "new array" statement takes a just 9 asm instructions (or even 7 for GCC). Here is another example - function that do many allocations in a loop to create a singly-linked list of arrays: |

NOINLINE void *create_list_of_arrays()

{

struct node

{

node *next;

std::array<int, 9> arr;

} *p = NULL;

for (int i=0; i<1000; i++)

{

node *n = new node;

n->next = p;

p = n;

}

return p;

} | mov eax,dword ptr fs:[0000002Ch]

push ebx

push esi

mov esi,dword ptr [eax]

push edi

xor edi,edi

add esi,128h

mov ebx,3E8h ; =1000 L2:

mov eax,dword ptr [esi]

test eax,eax

je L1 ; prob 1%

mov ecx,dword ptr [eax]

inc dword ptr [esi+8]

mov dword ptr [esi],ecx

dec ebx ; i++

mov dword ptr [eax],edi ; n->next = p;

mov edi,eax ; p = n;

jne L2 ; if (i<1000) goto L2 pop edi

pop esi

pop ebx

ret

L1:

... | ... L2:

mov r12,rax ; p = n;

mov rax,QWORD PTR fs:[rbx+0x258]

test rax,rax

je L1 ; prob 1%

mov rdx,QWORD PTR [rax]

add DWORD PTR fs:[rbx+0x268],0x1

mov QWORD PTR fs:[rbx+0x258],rdx

L3:

sub ebp,0x1 ; i++

mov QWORD PTR [rax],r12 ; n->next = p;

jne L2 ; if (i<1000) goto L2 add rsp,0x8

pop rbx

pop rbp

pop r12

pop r13

ret

L1:

mov edx,0x19

mov rsi,r13

mov edi,0x30

call <_Z24fetch_from_central_cache...>

jmp L3 |

For this case, compiler has optimized a whole "new node;" statement inside the loop to a mere 6 asm instructions!

I think, that execution speed of this resulting asm-code (generated for general enough C++ code) can quite compete with a good custom pool-based allocator implementation.

(Although, inlining can give some performance improvement, it is not extremely necessary, and even a regular call of ltalloc function still will be working very fast.)

2. Thread-efficiency and scalability.

To achieve high multithreading efficiency ltalloc uses an approach based on TCMalloc (I didn't take any code from TCMalloc, but rather just a main idea). So, there is per-thread cache (based on native thread_local variables). And all allocations (except the large ones, >56KB) are satisfied from the thread-local cache (just simple singly linked list of free blocks per size class).

If the free list of the thread cache is empty, then batch (256 or less) of memory blocks is fetched from a central free list (list of batches, shared by all threads) for this size class, placed in the thread-local free list, and one of blocks of this batch returned to the application. When an object is deallocated, it is inserted into the appropriate free list in the current thread's thread cache. If the thread cache free list now reaches a certain number of blocks (256 or less, depending on the block size), then a whole free list of blocks moved back to the central list as a single batch.

This simple batching approach alone gives enough scalability (i.e. with applicable low contention) for theoretically up to 128-core SMP system if memory allocation operations will be interleaved with at least 100 CPU cycles of another work (this is a rough average of single operation of moving batch to the central cache or fetch it from). And this approach especially effective for a producer-consumer pattern, when memory allocated in one thread then released on another.

3. Compact layout.

While most memory allocators store at least one pointer at the beginning (header) of each memory block allocated (so, for example, each 16 bytes (or even 13) block request actually wastes 32 bytes, because of 16B-alignment requirement), ltalloc rather just keeps a small header (64 bytes) per chunk (64KB by default), while all allocated blocks are just stored contiguously inside chunk without any metadata interleaved, which is much more efficient for small memory allocations.

So, if there is no any pointer at beginning of each block, there should be another way to find metadata for allocated objects. Some allocators to solve this problem keeps sbrk pointer, but this has such drawbacks as necessity to emulate sbrk on systems that don't support it, and that memory allocated up to sbrk limit can not be effectively returned to the system. So I decided to use another approach: all big blocks (obtained directly from the system) are always aligned to multiples of the chunk size, thus all blocks within any chunk will be not aligned as opposed to sysblocks, and this check can be done with simple if (uintptr_t(p)&(CHUNK_SIZE-1)), and pointer to chunk header is calculated as (uintptr_t)p & ~(CHUNK_SIZE-1). (Similar approach used in jemalloc.)

Finally, mapping of block size to corresponding size class is done via a simple approach of rounding up to the nearest "subpower" of two (i.e. 2n, 1.25*2n, 1.5*2n, and 1.75*2n by default, but this can be configured, and it can be reduced to exact power of two sizes), so there are 51 size classes (for all small blocks <56KB), and size overhead (internal fragmentation) is no more than 25%, in average 12%.

As a free bonus, this approach combined with contiguously blocks placement gives a "perfect alignment feature" for all memory pointers returned (see below).

FAQ

1. Is ltalloc faster than all other general purpose memory allocators?

Yes, of course, why else to start writing own memory allocator. :-)

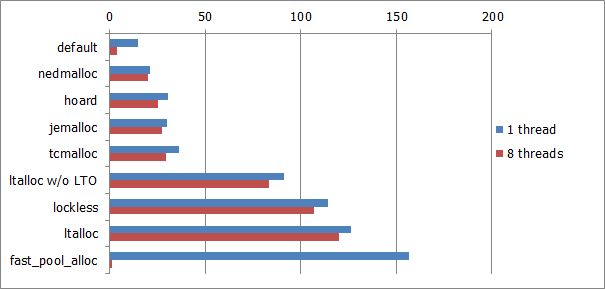

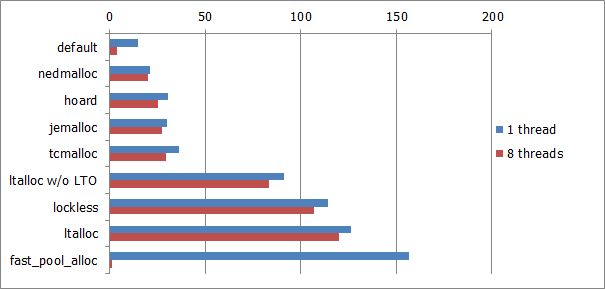

But, joking aside, let's look at the performance comparison table below (results obtained with this simple test, which is just continuously allocating and freeing memory blocks of 128 bytes size from simultaneously running threads).

(Results are given in millions of operations (pairs of alloc+free) per second for a single thread, i.e. to obtain a total amount of operations/sec, you should multiply corresponding result by the number of threads.)

| Sys. Configuration | | i3 M350 (2.3 GHz)

Windows 7 | | Core2 Quad Q8300

Windows XP SP3 | | i7 2600 (3.4 GHz)

Windows 7 | | 2x Xeon E5620 (2.4 GHz, 4 cores x 2)

Windows Server 2008 R2 | | 2x Xeon E5620 (2.4 GHz, 4 cores x 2)

Debian GNU/Linux 6.0.6 (squeeze) |

| Allocator \ Threads | | 1 | 2 | 4 (HT) | | 1 | 2 | 4 | | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 (HT) | | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 (HT) | | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 (HT) |

| default | | 10.0

(6.97) | 8.4

(8.04) | 5.3

(9.53) | | 8.3

(12.61) | 1.3

(79.23) | 0.4

(218.75) | | 16.0

(10.31) | 15.2

(10.86) | 13.3

(10.26) | 8.5

(10.73) | | 11.6

(9.53) | 11.2

(9.88) | 10.8

(9.70) | 10.7

(6.21) | 5.8

(10.45) | | 14.9

(8.49) | 14.9

(8.46) | 15.3

(8.25) | 4.8

(25.48) | 0.8

(79.00) |

| nedmalloc |

| 14.2

(4.91) | 13.1

(5.15) | 7.9

(6.39) | | 15.6

(6.71) | 15.6

(6.60) | 14.0

(6.25) | | 22.4

(7.37) | 22.3

(7.40) | 19.5

(6.99) | 13.0

(7.02) | | 16.7

(6.62) | 16.6

(6.67) | 16.4

(6.39) | 10.7

(6.21) | 8.4

(7.21) | | 22.5

(5.62) | 21.3

(5.92) | 21.8

(5.79) | 19.6

(6.24) | 11.3

(5.59) |

| Hoard |

| 32.2

(2.16) | 31.3

(2.16) | 23.8

(2.12) | | 44.7

(2.34) | 44.4

(2.32) | 40.3

(2.17) | | 77.6

(2.13) | 76.3

(2.16) | 64.0

(2.13) | 43.6

(2.09) | | 57.5

(1.92) | 56.2

(1.97) | 54.6

(1.92) | 34.2

(1.94) | 31.9

(1.90) | | 31.2

(4.05) | 30.4

(4.14) | 27.4

(4.61) | 25.3

(4.83) | 16.4

(3.85) |

| jemalloc |

| 11.5

(6.06) | 11.0

(6.14) | 7.0

(7.21) | | 13.4

(7.81) | 13.3

(7.74) | 5.0

(17.50) | | 18.2

(9.07) | 18.1

(9.12) | 10.1

(13.50) | 7.4

(12.32) | | 14.1

(7.84) | 14.0

(7.91) | 6.7

(15.64) | 4.4

(15.09) | 2.9

(20.90) | | 30.1

(4.20) | 30.0

(4.20) | 30.1

(4.20) | 27.9

(4.38) | 16.2

(3.90) |

| TCMalloc |

| 15.5

(4.50) | 13.9

(4.86) | 8.9

(5.67) | | 17.0

(6.16) | 16.7

(6.17) | 15.4

(5.68) | | 34.2

(4.82) | 34.0

(4.85) | 28.2

(4.84) | 18.1

(5.04) | | 21.6

(5.12) | 20.7

(5.35) | 20.1

(5.21) | 13.6

(4.88) | 10.2

(5.94) | | 36.5

(3.47) | 36.4

(3.46) | 33.5

(3.77) | 31.4

(3.89) | 18.6

(3.40) |

| ltalloc (w/o LTO) |

| 31.9

(2.18) | 31.0

(2.18) | 20.8

(2.43) | | 50.9

(2.06) | 50.9

(2.02) | 44.5

(1.97) | | 81.6

(2.02) | 79.7

(2.07) | 67.4

(2.02) | 48.1

(1.90) | | 62.2

(1.78) | 62.5

(1.77) | 62.1

(1.69) | 36.3

(1.83) | 31.1

(1.95) | | 91.1

(1.39) | 91.0

(1.38) | 90.9

(1.39) | 84.8

(1.44) | 46.8

(1.35) |

| lockless |

| 43.3

(1.61) | 40.3

(1.67) | 30.2

(1.67) | | The results are not available

(Windows Vista required) | | 88.7

(1.86) | 75.7

(2.18) | 75.4

(1.81) | 50.9

(1.79) | | 60.9

(1.81) | 61.1

(1.81) | 60.3

(1.74) | 39.9

(1.66) | 33.5

(1.81) | | 114.4

(1.11) | 107.6

(1.17) | 107.5

(1.17) | 102.0

(1.20) | 55.9

(1.13) |

| ltalloc |

| 69.7

(1.00) | 67.5

(1.00) | 50.5

(1.00) | | 104.7

(1.00) | 103.0

(1.00) | 87.5

(1.00) | | 165.0

(1.00) | 165.0

(1.00) | 136.4

(1.00) | 91.2

(1.00) | | 110.5

(1.00) | 110.7

(1.00) | 104.8

(1.00) | 66.4

(1.00) | 60.6

(1.00) | | 126.5

(1.00) | 126.0

(1.00) | 126.3

(1.00) | 122.3

(1.00) | 63.2

(1.00) |

| fast_pool_allocator |

| 116.5

(0.60) | 58.3

(1.16) | 12.5

(4.04) | | 152.0

(0.69) | 22.5

(4.58) | 5.6

(15.63) | | 277.8

(0.59) | 48.7

(3.39) | 25.1

(5.43) | 11.8

(7.73) | | 189.8

(0.58) | 62.0

(1.79) | 29.9

(3.51) | 3.9

(17.03) | 2.0

(30.30) | | 156.4

(0.81) | 11.5

(10.96) | 3.1

(40.74) | 1.3

(94.08) | 1.3

(48.62) |

Here is a chart for 2x Xeon E5620/Debian:

While this test is completely synthetic (and may be too biased), it measures precisely just an allocation/deallocation cost, excluding influence of all other things, such as cache misses (which are very important, but not always). So even this benchmark can be quite representative for some applications with small working memory set (which entirely fits inside cpu cache), or some specific algorithms.

2. What makes ltalloc so fast?

Briefly, that its ultimately minimalistic design and extremely polished implementation, especially minimization of conditional branches per a regular alloc call.

Consider a typical implementation of memory allocation function:

- if (size == 0) return NULL (or size = 1)

- if (!initialized) initialize_allocator()

- if (size < some_threshold) (to test if size requested is small enough)

- if (freeList) {result = freeList, freeList = freeList->next}

- if (result == NULL) throw std::bad_alloc() (for an implementation of operator new)

But in case of call to operator new overloaded via ltalloc there will be just one conditional branch (4th in the list above) in 99% cases, while all other checks are doing only when necessary in the remaining 1% rare cases.

rmem

3. Does ltalloc return memory to the system automatically?

Well, it is not (except for large blocks).

But you can always call ltalloc_squeeze() manually at any time (e.g., in separate thread), which almost have no any impact on performance of allocations/deallocations in the others simultaneously running threads (except the obvious fact of having to re-obtain memory from the system when allocating new memory after that). And this function can release as much memory as possible (not only at the top of the heap, like malloc_trim does).

I don't want doing this automatically, because it highly depends on application's memory allocation pattern (e.g., imagine some server app that periodically (say, once a minute) should process some complex user request as quickly as possible, and after that it destroys all objects used for processing - returning any memory to the system in this case may significantly degrade performance of allocation of objects on each new request processing). Also I dislike any customizable threshold parameters, because it is usually hard to tune optimally for the end user, and this has some overhead as some additional checks should be done inside alloc/free call (non necessary at each call, but sometimes they should be done). So, instead I've just provided a mechanism to manually release memory at the most appropriate time for a specific application (e.g. when user inactive, or right after closing any subwindow/tab).

But, if you really want this, you can run a separate thread which will just periodically call ltalloc_squeeze(0). Here is one-liner for C++11:

std::thread([] {for (;;ltalloc_squeeze(0)) std::this_thread::sleep_for(std::chrono::seconds(3));}).detach();

4. Why there are no any memory statistics provided by the allocator?

Because it causes additional overhead, and I don't see any reason to include some sort of things into such simple allocator.

Anyway there will be some preprocessor macro define to turn it on, so you can take any suitable malloc implementation and optionally hook it up in place of ltalloc with preprocessor directives like this:

#ifdef ENABLE_ADDITIONAL_MEMORY_INFO

#include "some_malloc.cxx"

#else

#include "ltalloc.cc"

#endif

5. Why there is no separate function to allocate aligned memory (like aligned_alloc)?

Just because it's not needed! :)

ltalloc implicitly implements a "perfect alignment feature" for all memory pointers returned just because of its design.

All allocated memory blocks are automatically aligned to appropriate the requested size, i.e. alignment of any allocation is at least pow(2, CountTrailingZeroBits(objectSize)) bytes. E.g., 4 bytes blocks are always 4 bytes aligned, 24 bytes blocks are 8B-aligned, 1024 bytes blocks are 1024B-aligned, 1280 bytes blocks are 256B-aligned, and so on.

(Remember, that in C/C++ size of struct is always a multiple of its largest basic element, so for example sizeof(struct {__m128 a; char s[4];}) = 32, not 20 (16+4) ! So, for any struct S operator "new S" will always return a suitably aligned pointer.)

So, if you need a 4KB aligned memory, then just request (desired_size+4095)&~4095 bytes size (description of aligned_alloc function from C11 standard already states that the value of size shall be an integral multiple of alignment, so ltalloc() can be safely called in place of aligned_alloc() even without need of additional argument to specify the alignment).

But to be completely honest, that "perfect alignment" breaks after size of block exceeds a chunk size, and after that all blocks of greater size are aligned by the size of chunk (which is 64KB by default, so, generally, this shouldn't be an issue).

Here is a complete table for all allocation sizes and corresponding alignment (for 32-bit platform):

| Requested size | Alignment | | Requested size | Alignment | | Requested size | Alignment | | Requested size | Alignment |

| 1..4 | 4 | | 81..96 | 32 | | 769..896 | 128 | | 7169..8192 | 8192 |

| 5..8 | 8 | | 97..112 | 16 | | 897..1024 | 1024 | | 8193..10240 | 2048 |

| 9..12 | 4 | | 113..128 | 128 | | 1025..1280 | 256 | | 10241..12288 | 4096 |

| 13..16 | 16 | | 129..160 | 32 | | 1281..1536 | 512 | | 12289..14336 | 2048 |

| 17..20 | 4 | | 161..192 | 64 | | 1537..1792 | 256 | | 14337..16384 | 16384 |

| 21..24 | 8 | | 193..224 | 32 | | 1793..2048 | 2048 | | 16385..20480 | 4096 |

| 25..28 | 4 | | 225..256 | 256 | | 2049..2560 | 512 | | 20481..24576 | 8192 |

| 29..32 | 32 | | 257..320 | 64 | | 2561..3072 | 1024 | | 24577..28672 | 4096 |

| 33..40 | 8 | | 321..384 | 128 | | 3073..3584 | 512 | | 28673..32768 | 32768 |

| 41..48 | 16 | | 385..448 | 64 | | 3585..4096 | 4096 | | 32769..40960 | 8192 |

| 49..56 | 8 | | 449..512 | 512 | | 4097..5120 | 1024 | | 40961..49152 | 16384 |

| 57..64 | 64 | | 513..640 | 128 | | 5121..6144 | 2048 | | 49153..57344 | 8192 |

| 65..80 | 16 | | 641..768 | 256 | | 6145..7168 | 1024 |

Blocks of size greater than 57344 bytes are allocated directly from the system (actual consumed physical memory is a multiple of page size (4K), but virtual is a multiple of alignment - 65536 bytes).

6. Why big allocations are not cached, and always directly requested from the system?

Actually, I don't think that caching of big allocations can give significant performance improvement for real usage, as simple time measurements show that allocating even 64K of memory directly with VirtualAlloc or mmap is faster (2-15x depending on the system) than simple memset to zero that allocated memory (except the first time, which takes 4-10x more time because of physical page allocation on first access). But, obviously, that for greater allocation sizes, overhead of the system call would be even less noticeable. However, if that really matters for your application, then just increase constant parameter CHUNK_SIZE to a desired value.

Usage

GNU/Linux

- gcc /path/to/ltalloc.cc ...

- gcc ... /path/to/libltalloc.a

- LD_PRELOAD=/path/to/libltalloc.so <appname> [<args...>]

For use options 2 and 3 you should build libltalloc:

hg clone https://code.google.com/p/ltalloc/

cd ltalloc/gnu.make.lib

make

(then libltalloc.a and libltalloc.so files are created in the current directory)

And with this options (2 or 3) all malloc/free routines (calloc, posix_memalign, etc.) are redirected to ltalloc.

Also be aware, that GCC when using options -flto and -O3 with p.2 will not inline calls to malloc/free until you also add options -fno-builtin-malloc and -fno-builtin-free (however, this is rather small performance issue, and is not necessary for correct work).

Windows

Unfortunately, there is no simple way to override all malloc/free crt function calls under Windows, so far there is only one simple option to override almost all memory allocations in C++ programs via global operator new override - just add ltalloc.cc file into your project and you are done.

ltalloc was successfully compiled with MSVC 2008/2010/2012, GCC 4.*, Intel Compiler 13, Clang 3.*, but it's source code is very simple, so it can be trivially ported to any other C or C++ compiler with native thread local variables support. (Warning: in some builds of MinGW there is a problem with emutls and order of execution of thread destructor (all thread local variables destructed before it), and termination of any thread will lead to application crash.)